Zero-Dependency NodeJS Logging

The Scenario

As a JavaScript developer, you’ve probably encountered a situation where you’re trying to troubleshoot something. There are a variety of thorough, robust tools out there that you could use to debug things, but… console.log() exists.

This article isn’t about “debuggers vs print/log”, but the above is brought up to highlight that even with whatever amazing debugging tools are out there, developers still just log or print.

Putting in a console.log() statement to identify what exact piece of data is in whichever variable is the source of your problem is a convenient way to work through a problem, for sure. But then after the problem is done and solved, what do you do with that console.log() statement?

Do you delete the console.log() lines?

Do you comment them out?

Do you leave them in your code so that your production app has those logs too?

This leads us to…

The Problem

It’s definitely easy to go “it’s JavaScript, there’s no strict rules about this” and carry on as if this has no impact on the project. But as it turns out, littering a bunch of console.log statements throughout your work does matter.

- Using a console.log() statement has a performance impact

- Doing something costs more than not doing something, and that’s fine. That’s fair. It just means that developers need to be smart about when and what they’re logging, and reduce the number of log statements that end up in the production build of an application. It’s easy for developers to not keep that in mind though.

- JavaScript in particular has a very slow console.log() function. You can find examples such as this: Why You Should Think Twice Before Using console.log, and Tips for Avoiding Performance Pitfalls, by Zack (Medium user @xiaweiliang94), published to Medium on 16th March 2023

- Developers don’t always use console.log() consistently.

- Developers typically benefit from seeing data, to figure out the solution to their problems. But not all developers know what data they need, or where to get that data.

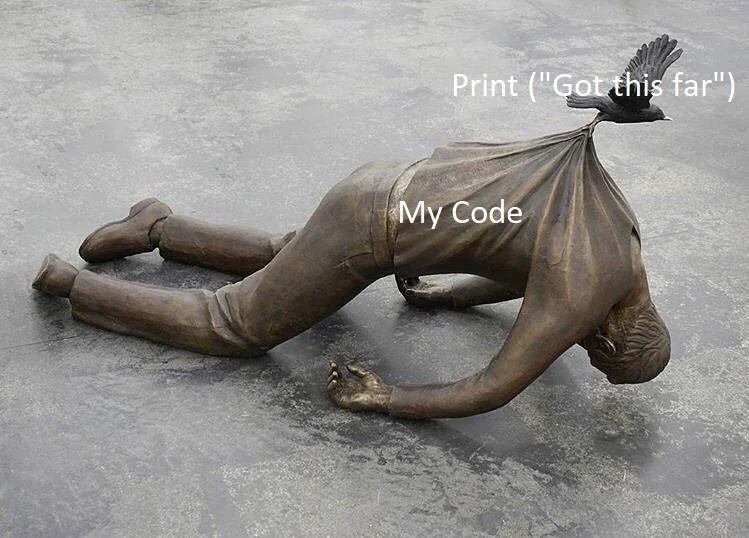

- It’s been meme’d a lot in programming groups online, but it’s typical to see console.log(“code reached here”)-type log statements. That doesn’t tell others much about what problems may have occured in the code.

- Developers don’t always remove or comment-out their usage of console.log() consistently.

- Things like commenting-out or deleting the log statements take time, and it’s easy to miss a log statement when you’re manually going through and removing them.

- Developers creating packages need to be aware of the down-stream impacts of their logging choices.

- If you’re creating an NPM package, project template, or other similarly-reusably bundle of code, then you need to make sure your logs don’t clutter the logs of other developers.

- Ideally, you would even create some flags or settings to let other developers opt-in to enabling your project’s logging, so they can troubleshoot their own usage of your code.

There are better ways to log, especially when using logging for reasonable and useful purposes. This article will show a native, built-in NodeJS approach to useful logging.

The “Typical” Solutions

There are two typical solutions I’ve seen to this problem online:

- Use a NPM package to handle logging and never use

console.log()in your code ever again, instead using the NPM package’s log function. - Replace

console.log()with a null value or stub function if the process.env.NODE_ENV environment variable is set to production so nothing is ever logged in production builds of the app. Both of those solutions have their positives and negatives.

If you use an NPM package, regardless of how amazing that package may be - you are introducing additional dependencies into your project.

That might sound like a bunch of harmless fluff that’ll never happen to you or your work, but you need to remember: one of the most-infamous dependency-based exploits in the software world was log4j: a logging framework for Java (not JavaScript!) applications. That exploit gave malicious actors the ability to run their own code on your machine, perform DDOS operations using your machine, or just do whatever they want to your machine via code. It was a big, dangerous thing that impacted numerous software products across the world. You can find the Australian Signals Directorate’s page on the Log4j vulnerability here: https://www.cyber.gov.au/about-us/advisories/2021-007-log4j-vulnerability-advice-and-mitigations

And the second solution; removing console.log() from production builds… well, that’s not exactly useful for troubleshooting production builds, is it? If you do want to try that yourself, it’s covered in the same Medium article that I referenced earlier about console.log() statements being slow in our code - here: Why You Should Think Twice Before Using console.log, and Tips for Avoiding Performance Pitfalls, by Zack (Medium user @xiaweiliang94), published to Medium on 16th March 2023

The Built-In Solution

So, if we want to log but want to avoid external dependencies, what can we do?

As it turns out, NodeJS has had some form of built-in debug and logging system since its earliest of early days.

In 2024-era versions of NodeJS, we want to use functions like debug or debuglog from the node:util standard library. Early versions of this would’ve used debug or log functions from that same standard library - functions to do what we need to do stretch back to extremely early versions of NodeJS, as far back as 0.10.x!

Let’s dive into what this standard NodeJS library can let us do.

// Import the NodeJS standard library for "util"

const util = require("node:util");

// Initialise a debug logger that is activated by a certain value

// being detected in process.env.NODE_DEBUG

const someLogger = util.debuglog("debugTrigger");

// Call the logger and give it string-able content to log that content.

someLogger("Starting someLogger");

// Even string coersion works too:

let someNumber = 3 * 3;

someLogger(someNumber);

// And objects:

let someObject = {

name: "Alex",

powerLevel: 9001

}

someLogger(someObject);

// Basically, if it has some sort of "toString" function on it,

// and basically everything does by default, even just internally,

// then it'll get logged just fine.

// Just like the normal console.log function.

someLogger("Tada! Works just like console.log()!");Now, there’s a catch. If we want to see that logger do its logging, we need to run our code with a specific value set to an environment variable.

We have to set NODE_DEBUG to be debugtrigger, since that is what the util.debuglog() function was given as its trigger value.

If that value isn’t set, the logger won’t log. That’s not a bad thing entirely, but if we want to see the cool thing happen then we need to run our code with:

NODE_DEBUG=debugtrigger node src/index.js

The command above assumes the code example above is stored in “src/index.js” in a project.

When we run that, we’ll get this output:

DEBUGTRIGGER 115308: Starting someLogger

DEBUGTRIGGER 115308: 9

DEBUGTRIGGER 115308: { name: ‘Alex’, powerLevel: 9001 }

DEBUGTRIGGER 115308: Tada! Works just like console.log()!

You can see that the trigger value for the logger becomes its identifier, alongside the process ID of the code that was running. This might not be that useful on its own, which is why this system really shines when multiple loggers are in play.

Consider this code:

// Import the NodeJS standard library for "util"

const util = require("node:util");

// Initialise a debug logger that is activated by a certain value

// being detected in process.env.NODE_DEBUG

const someLogger = util.debuglog("debugTrigger");

const someOtherLogger = util.debuglog("bananas");

const pokemonLogger = util.debuglog("pokemon");

// Call the logger and give it string-able content to log that content.

someLogger("Starting someLogger");

someOtherLogger("Starting someOtherLogger");

pokemonLogger("Starting pokemonLogger");Running that code with the exact same command as before is going to give us very underwhelming output:

DEBUGTRIGGER 116802: Starting someLogger

To let multiple loggers work simultaneously, the NODE_DEBUG variable is actually meant to be used as a comma-separated string. That means multiple logger trigger values can be specified, like so:

NODE_DEBUG=debugtrigger,pokemon node src/exampleUtilLogger.js

That’ll give us this output:

DEBUGTRIGGER 117713: Starting someLogger

POKEMON 117713: Starting pokemonLogger

Because the NODE_DEBUG variable was not given a value of “bananas” as one of its comma-separated values, the “someOtherLogger” logger did not run.

Now, to make use of this within the wider codebase of whatever project we’re working on, we just need to do three things:

- Export the logger functions.

- Import the logger functions in the files that need to use them.

- Use the imported logger functions in the same way that you would normally use console.log() functions.

Brace yourself, let’s look at an example of this in action!

Practical Usage of the Built-In Solution

I’m working on an object-document mapper package called “SuperCamo”. It’s an ODM for NeDB - an embedded database alternative to MongoDB. You can take a look at it over here on NPM, or here on GitHub.

As I’m learning, it’s actually really tricky to make your own database data modeller/mapper/manager/etc. I need to keep track of data as it moves through my system, without specifying or hard-coding very many things. It’s a lot of generic code so that developers can go and make their own database models and schemas and so on.

This means that I want a lot of logging, but I don’t want to force that on to any developer that uses my package. So, I added a logging function to the package:

const log = {

verbose: util.debuglog("verbose"),

superCamo: util.debuglog("supercamo"),

superCamoDocument: util.debuglog("supercamo:document"),

superCamoEmbeddedDocument: util.debuglog("supercamo:embeddeddocument"),

superCamoBaseDocument: util.debuglog("supercamo:basedocument"),

superCamoClient: util.debuglog("supercamo:client"),

superCamoValidators: util.debuglog("supercamo:validators"),

}

log.verbose("Starting SuperCamo with verbose logging enabled.");

log.superCamo("Starting SuperCamo with SuperCamo-specific verbose logging enabled.");

log.superCamoDocument("Starting SuperCamo with SuperCamo 'Document-specific verbose logging enabled.");

log.superCamoEmbeddedDocument("Starting SuperCamo with SuperCamo 'Embedded Document'-specific verbose logging enabled.");

log.superCamoBaseDocument("Starting SuperCamo with SuperCamo 'Base Document'-specific verbose logging enabled.");

log.superCamoClient("Starting SuperCamo with SuperCamo client-specific verbose logging enabled.");

log.superCamoValidators("Starting SuperCamo with SuperCamo validator-specific verbose logging enabled.");

/**

* Configured logging system for the SuperCamo package.

*

* Pass a string to this, and it'll automatically figure out which NodeJS util.DebugLogger to use.

* @author BigfootDS

*

* @param {String} message The string to log.

* @param {("Client"|"BaseDocument"|"Document"|"EmbeddedDocument"|"Validators"|"")} caller Specific string to help with conditional logging, eg. "Client" to allow the SuperCamoClient logger to log. Defaults to "", which will allow the SuperCamo catch-all logger and Verbose generic logger to log.

*/

function SuperCamoLogger(message, caller = "") {

if (log.superCamo.enabled){

log.superCamo(message);

} else if (log.verbose.enabled){

log.verbose(message);

} else {

switch (caller) {

case "Client":

log.superCamoClient(message);

break;

case "BaseDocument":

log.superCamoBaseDocument(message);

break;

case "Document":

log.superCamoDocument(message);

break;

case "EmbeddedDocument":

log.superCamoEmbeddedDocument(message);

break;

case "Validators":

log.superCamoValidators(message);

break;

default:

break;

}

}

}

module.exports = SuperCamoLogger;Note: Since writing this article, I’ve overhauled SuperCamo to be written in TypeScript. So if you dig into the GitHub repository, the code might look a little different!

You’ll notice a few things going on here:

- Each logger is declared in a

logobject.- This is useful if you just want to export and use the loggers directly in your code - I don’t, but that may change, so I didn’t want to limit myself here. Keeping options like that open make a package easier to maintain and update over time.

- There are SuperCamo-specific logger trigger values, as well as a generic “verbose” trigger value.

- This lets a developer just go

NODE_DEBUG=verboseand see all logs if they want to, which would be useful when they first begin troubleshooting and don’t know where there issues are coming from. - This also lets developers re-run the code with more and more fine-grained logging control if they need that. Maybe they know the issue is coming from SuperCamo, but are not sure if it’s a database client problem or a database model problem - they can toggle the loggers to narrow things down.

- This lets a developer just go

- There is an order of operations or control flow to make sure that if multiple loggers are enabled, the most-suitable one is the only one to log the message.

- The logic basically prefers the “supercamo” logger if both the “supercamo” and “verbose” loggers are enabled, so that SuperCamo logging stays distinct from any other code that might be using a “verbose” logger.

- The wrapping function receives an argument that is just a way for other code to say what class is calling the logger. So the “caller” being set to “Client” means that the database client class is calling the logger. This allows specific chunks of code to be logged distinctly from other chunks of code.

- The logic prefers the “supercamo” logger if both the “supercamo” and any of the “supercamo:feature” loggers are enabled, as a passive reminder to developers that they should be using either the one generic logger or any mix of the specific loggers - but not a mix of generic and specific loggers.

That SuperCamoLogger function is then exported, for other files to import and use in place of any console.log() statement.

const SuperCamoLogger = require("../../utils/logging.js");

// Code omitted for brevity.

// This is a snippet of a static "create" method in a Document class.

// It creates a Document instance, validates the data, and returns the valid instance.

let newInstance = new this(dataObj, incomingParentDatabaseName, incomingCollectionName);

if (validateOnCreate){

try {

let isValid = await newInstance.#validate();

let newInstanceData = await newInstance.getData();

SuperCamoLogger("This document is valid:", "BaseDocument");

SuperCamoLogger(newInstanceData, "BaseDocument");

} catch (error) {

throw error;

}

}

return newInstance;

// Code omitted for brevity.In the code above, an entire NoSQL document is logged froms line 13-14 if logging is enabled. This could pollute the output of an app very quickly, so it’s important to make sure that those logs are opt-in only. When developers need to see if their documents are being created correctly, they can just set an appropriate NODE_DEBUG value.

Because the logic for determining which logger needs to log the message is handled within the SuperCamoLogger function internally, it keeps the logging system “dry” - no repeated logic for figuring out which content gets logged where. Other files would use something other than “BaseDocument” as the second argument of the logger function to make use of that functionality.

As an example of what this means for dependent projects, here’s a comparison of what SuperCamo’s output looked like before and after I implemented that logger system.

The usage of the package can be as simple as this:

const SuperCamo = require("@bigfootds/supercamo");

const path = require("node:path");

class User extends SuperCamo.NedbDocument {

constructor(data, databaseName, collectionName){

super(data, databaseName, collectionName);

this.email = {

type: String,

required: true

}

}

}

async function doThings(){

let exampleDb = await SuperCamo.connect(

"SomeDatabaseName",

path.join(process.cwd(), "databases"),

[

{name: "Users", model: User}

]

);

let newUser = await exampleDb.insertOne("Users", {name:"Alex", email:"test@email.com"})

console.log(newUser.toString());

}

doThings();Note that there’s just one console.log() statement in that code on line 25 - that’s to represent the end “user” or developer who is using my work as a dependency, doing their own usual logging.

Here’s the terminal output of the above code from before the logger system was implemented, where SuperCamo was using console.log() everywhere internally:

node src/index.js

Validating _id with value of undefined.

Validating email with value of test@email.com.

This document is valid:

{ email: ‘test@email.com’ }

insertOne insert result:

{ email: ‘test@email.com’, _id: ‘MmqtzQySw9mvAWJZ’ }

insertOne tempInstance result:

User {

_id: { type: [Function: String], required: false },

email: { type: [Function: String], required: true }

}

Validating _id with value of MmqtzQySw9mvAWJZ.

Validating email with value of test@email.com.

This document is valid:

{ _id: ‘MmqtzQySw9mvAWJZ’, email: ‘test@email.com’ }

{“_id”:“MmqtzQySw9mvAWJZ”,“email”:“test@email.com”}

Here’s the terminal output of the above code from after the logger system was implemented:

node src/index.js

{“_id”:“YStk0wOxwVn9NNAD”,“email”:“test@email.com”}

…that’s a huge difference, and a massively positive impact on developer’s quality of life as they use this code.

The output can be customised as per the logger’s compatible NODE_DEBUG values, so here’s the same code run again but with NODE_DEBUG set to “supercamo”:

NODE_DEBUG=supercamo node src/index.js

SUPERCAMO 5732: Starting SuperCamo with SuperCamo-specific verbose logging enabled.

SUPERCAMO 5732: Validating _id with value of undefined.

SUPERCAMO 5732: Validating email with value of test@email.com.

SUPERCAMO 5732: Document’s data after validation:

SUPERCAMO 5732: { name: ‘Alex’, email: ‘test@email.com’ }

SUPERCAMO 5732: This document is valid:

SUPERCAMO 5732: { email: ‘test@email.com’ }

SUPERCAMO 5732: insertOne insert result:

SUPERCAMO 5732: { email: ‘test@email.com’, _id: ‘9X8caQHrVBCYgiKA’ }

SUPERCAMO 5732: insertOne tempInstance result:

SUPERCAMO 5732: User {

_id: { type: [Function: String], required: false },

email: { type: [Function: String], required: true }

}

SUPERCAMO 5732: Validating _id with value of 9X8caQHrVBCYgiKA.

SUPERCAMO 5732: Validating email with value of test@email.com.

SUPERCAMO 5732: Document’s data after validation:

SUPERCAMO 5732: { email: ‘test@email.com’, _id: ‘9X8caQHrVBCYgiKA’ }

SUPERCAMO 5732: This document is valid:

SUPERCAMO 5732: { _id: ‘9X8caQHrVBCYgiKA’, email: ‘test@email.com’ }

{“_id”:“9X8caQHrVBCYgiKA”,“email”:“test@email.com”}

And an example of the generic “verbose” flag being used:

NODE_DEBUG=verbose node src/index.js

VERBOSE 6640: Starting SuperCamo with verbose logging enabled.

VERBOSE 6640: Validating _id with value of undefined.

VERBOSE 6640: Validating email with value of test@email.com.

VERBOSE 6640: Document’s data after validation:

VERBOSE 6640: { name: ‘Alex’, email: ‘test@email.com’ }

VERBOSE 6640: This document is valid:

VERBOSE 6640: { email: ‘test@email.com’ }

VERBOSE 6640: insertOne insert result:

VERBOSE 6640: { email: ‘test@email.com’, _id: ‘DjjYkqRJ5fewhZr2’ }

VERBOSE 6640: insertOne tempInstance result:

VERBOSE 6640: User {

_id: { type: [Function: String], required: false },

email: { type: [Function: String], required: true }

}

VERBOSE 6640: Validating _id with value of DjjYkqRJ5fewhZr2.

VERBOSE 6640: Validating email with value of test@email.com.

VERBOSE 6640: Document’s data after validation:

VERBOSE 6640: { email: ‘test@email.com’, _id: ‘DjjYkqRJ5fewhZr2’ }

VERBOSE 6640: This document is valid:

VERBOSE 6640: { _id: ‘DjjYkqRJ5fewhZr2’, email: ‘test@email.com’ }

{“_id”:“DjjYkqRJ5fewhZr2”,“email”:“test@email.com”}

As the above shows - thorough logging can be enabled, but by default will not be enabled and will not intrude on a developer’s usage of my code.

Summary

This was a fun little rabbit hole for me to explore, and I hope this write-up has been useful for you as well!

Logging systems are a very useful thing to implement - even if you do use a pre-made NPM package to do so. Logging is better than rough console.log() usage, and console.log() usage is better than no logs or outputs at all.

If this has helped you think of new ways to log in your own work, then definitely give it a shot. Putting this stuff into practice is the best way to master it!