Helping Others Cite, Reference, or Attribute Your Software

A note for Coder Academy students.

This article can be used as an example for Coder Academy’s assessment item, “Technical Blog Post and Prototype”, for the ISK1002 Industry Skills 2 subject. I’ve kept this article focused on the rubric where I can, not necessarily the assessment brief - the rubric is what you’ll be graded on, after all!

For a walkthrough of how this article maps to the rubric, click this text.

- At least two referenced external sources to support an explanation of an industry-relevant trend or opportunity

- Rise of “CI/CD/CC” movement

- Platforms like Github increasing the ease of citations/referencing/attribution with new features

- Explanation of the CodeMeta project metadata format and the Citation File Format

- At least two referenced external sources to support an explanation of an industry-relevant ethical issue in detail

- The importance of licensing/copyright/referencing/attribution

- Reiterate some of of the info CodeMeta explains for their data format

- At least two referenced external sources to support an explanation of a problem or scenario and solution to the problem or scenario

- Problem: Lack of developer awareness about these tools, hurdles that stop developers implementing such “simple” things in their work

- Solution: Demonstrate how to implement CodeMeta and CFF files in software projects

- Article should include a plan covering the steps required to address the problem or scenario

- Tutorial on how to implement CodeMeta and CFF files in software projects

- Brief example of how CodeMeta/CFF data can be used in projects (e.g. read in a version number, contributors array, etc, to display in appropriate UI of an app)

- Identify the essential skills, knowledge, tools, etc, required to implement the solution to the problem or scenario, explain why those are needed, identify alternatives to those identified things, and explain why the chosen things are used in the solution instead of the alternatives.

- Comparison of metadata formats (e.g. using CodeMeta “crosswalks” to highlight gaps in some formats)

- Show how GitHub currently supports CFF and has plans to support future formats (link to GitHub issues/discussions where this popped up)

- No formatting issues, and uses correct spelling & grammar throughout the article.

- This can be as “manual” as just spell-checking everything yourself, but I like automation. I’ve implemented a GitHub Action that runs two spelling & grammar tools: ReviewDog’s “misspell” action and ReviewDog’s “languagetool” action. They’ll validate and suggest fixes for the articles I write into this blog repository.

- Creates code with comments, comments are relevant to the project, comments are all easy to understand, and ideally stick to a specific commenting or documentation style.

- JSDoc comments to cover syntax-related commenting automatically, plus manually-written descriptions inserted into those JSDoc comments.

Each top-level dot point in the list above matches one rubric item (or rubric row, however you want to call it) in the assessment. If you’re working on this assessment yourself, you may benefit from planning things out in a similar list! Or at least, including a similar list into your work will help any assessment graders to see everything that you’re intending to show.

And no, this article does not get perfect marks for the rubric. I’ve got other things to do with my time!

This article might meet a high distinction overall, almost definitely a distinction overall at least.

You can see how this article was written in the repository source code, here:

Yes, it’s a Markdown Extended file - it’s part of a website built with the Astro framework. It is deployed via Netlify.

Stumbling Into Licensing and Attribution

In all areas of software development, we developers will encounter and use licenses whether it’s purposefully and explicit or not.

Doing something like installing a package from NPM exposes us to the license of that package.

And doing something like activating an installation of a game engine such as Unity and Unreal exposes us to a license of that engine.

We see licenses more than we might think. But these licenses are typically more about protecting ownership of work and determining how a piece of code is used.

Attribution is the way that we can know who we’re working with through those external packages and tools. It’s more about crediting a creator for their creations.

We can’t really, completely, use licensing and attribution interchangeably. A lot of the data they may cover may be the same, but they branch apart and veer into different territories with different information added past their shared bits of data.

For example, an open-source project could be using the MIT license. If your own project uses that open-source project as a dependency, your compiled or deployed project must still contain a copy of that open-source project’s license and copyright notices.

So, the license determines a legal obligation about your usage of someone else’s work.

Attribution, on the other hand, can be covered by that same obligation… sometimes.

There’s a variant of the MIT license out there known as MIT No Attribution, where the only difference is that your own project does not need to include a copy of the license or copyright notices from whatever other project you’re dependent on.

So, a license can still be in effect without attribution.

And the flipped scenario: what if a project is using something like The Unlicense? There is no attribution data provided by that license, since it provides no copyright information or any other license information.

If you chose to still attribute a project like that (because you’re a good cookie who wants to shine lights on the pillars that your work is built upon, appropriately crediting people who aided your work), you would need to figure out a heap of information about the developers of that work and create your own attribution statement for that project.

Doing that, manually, for every project, will lead to chaos. The way you manually make attribution data may differ from how someone else makes attribution data. If people are out there making attribution statements that wildly differ to everybody else’s attribution statements, how do you determine that you’ve covered things appropriately?

Wait, what?

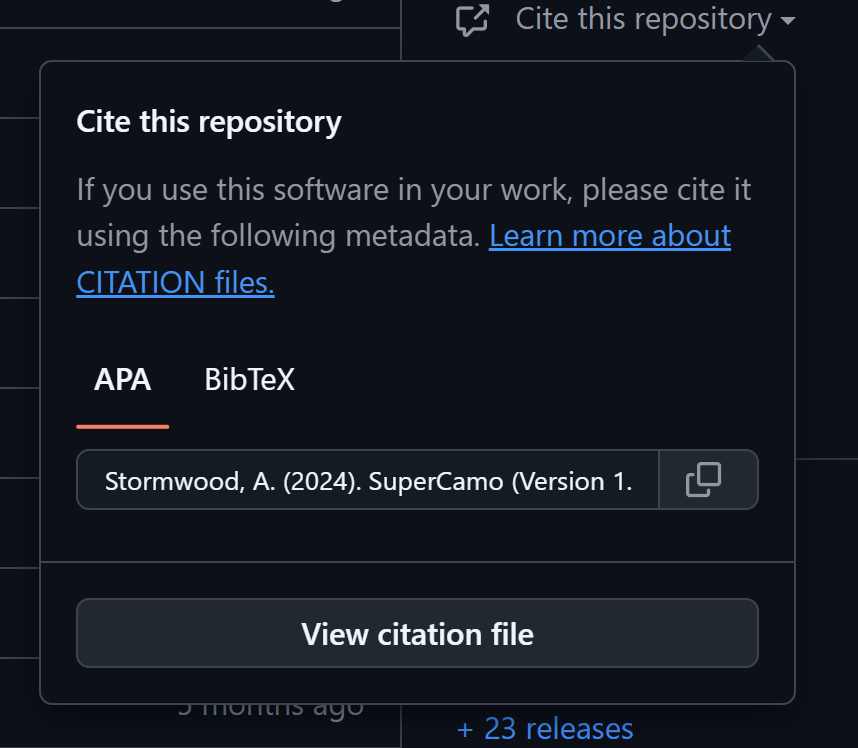

One day, when digging into some GitHub documentation to read up about customising some profile pages, I found this interesting page on CITATION files. 2

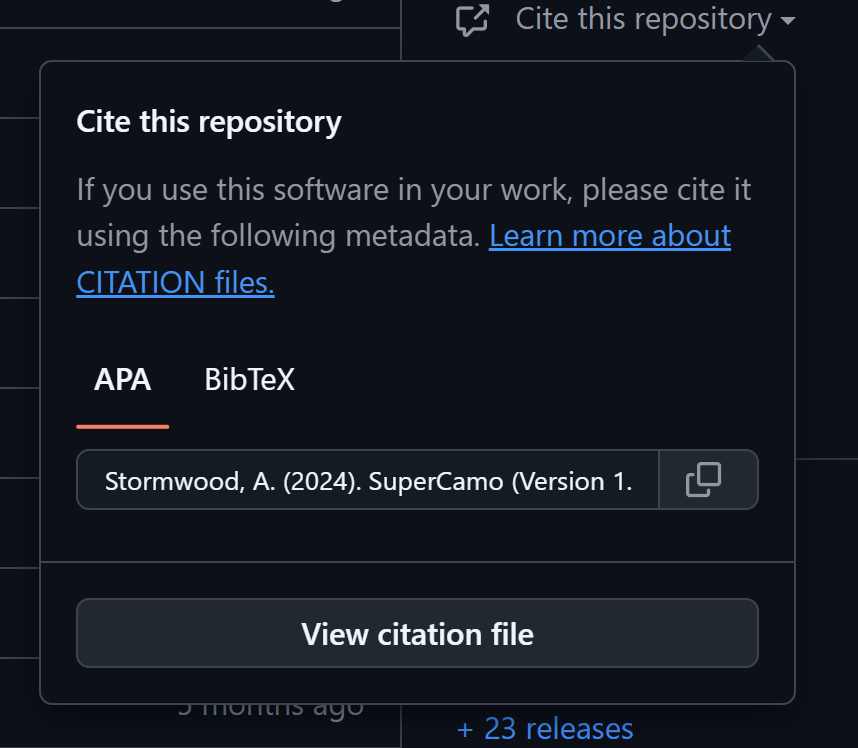

A CITATION file allows a repository to conveniently provide a way for anyone to correctly attribute a repository. The convenient result is something like this:

I’ll dig into exactly how those citation files work later in this article, but I just wanted to show off the end-result for now. It’s super convenient! It even supports repositories containing things other than software! 4

But, why?

Citations, referencing, attribution, and licensing all help others use your work.

And potentially more-importantly than that: they help others learn from your work.

As a university educator for my day job, learning is a big deal to me. Any student, researcher, teacher, or other academically-involved person will typically need to cite and reference the works of others as part of their activities. As UNSW states with multiple nuggets of wisdom5:

By citing the work of a particular scholar, you acknowledge and respect the intellectual property rights of that researcher.

And…

Referencing is a way to provide evidence to support the assertions and claims in your own assignments.

And…

By citing experts in your field, you are showing your marker that you are aware of the field in which you are operating.

And my favourite, most-creative statement on that page:

Your citations map the space of your discipline and allow you to navigate your way through your chosen field of study, in the same way that sailors steer by the stars.

Even third-party or archival systems such as Zenodo6 create and integrate citation data into anything you put into their systems. They have multiple features involved in archiving and organising whatever works are uploaded to their platform, including the usage of any existing citation data and creation of “digital object identifiers”. I would fully expect that they’re adhering to the idea of “if it’s not organised, then its preservation is useless as we have no way to identify or find it” - a thought I’ve had while managing my own data hoard in a home server.

All of the above means well in an academic sense, of course, but for those more in an active industry setting (e.g. developers, programmers, managers, team leads), please consider:

Using references helps justify things.

Going around saying “we need to upgrade this project because there’s a bug that hackers are using” might scare some clueless folks into listening to you, but an a more-experienced workplace you might get a response of “says who?” or “what’s the CVE?” or “has it been patched yet?” or “what’s the hack and how does it work? Is it a realistic threat?”

All of those questions are best handled by going: “Here’s the notice from Blah Blah Cyber Security Group”. That’s a reference to an expert, external piece of information.

Now, the above example puts all of that in a casually-framed verbal dialogue - but if you ever need to create a paper trail (either as emails, reports, or other documents), then you need a way to link or reference or cite what you’re saying. So you’re back to these same systems that academics and students are using.

Project Metadata

So, this brings us to project metadata. Our local dears at the Australiab Bureau of Statistics define metadata as7:

Metadata is the information that defines and describes data.

It is often referred to as data about data or information about data because it provides data users with information about the purpose, processes, and methods involved in the data collection.

This means that metadata, in the context of software development, is information about your software project. This is important! It’s important because metadata helps us easily figure out things about our project.

Specifically, we can use metadata to figure out any citation data about our projects.

And even more amazingly: we can use metadata to automatically generate and update any citation data about our projects.

Think about what a citation needs. For example, if you were citing an article from a website (such as a news article or even this page that you’re reading right now) in an APA7 citation format, you would need these pieces of information:

- Author Name, first and last.

- Date

- Article Title

- Website Name

- Article URL

Citing this webpage would look like:

Stormwood, A. (2025, March 25). Helping Others Cite, Reference, or Attribute Your Software. Alex Stormwood. https://alexstormwood.com/articles/helpingothersciteyoursoftware/

When we cite software, we need these pieces of information:

- Author Name, first and last.

- Date

- Project Title

- Project Version

- Project Type

- Project URL

Not all of that is commonly implemented in typical referencing generator websites. For example, this website you’re viewing now - its GitHub repository would be cited like this:

Alex Stormwood. (2023). GitHub - AlexStormwood/alexstormwood.com: Personal blog. GitHub. https://github.com/AlexStormwood/alexstormwood.com

…but that’s according to MyBib.com, a great website but they unfortunately do not have software citation implemented at the time of writing. It means that they will process the repository web page as if it’s a standard website or article - so not everything is super descriptive or clear. Like, the project title? We don’t need the GitHub repository identifier there, or the repository description. We can use a proper title.

We can customise this stuff.

We can set up more-descriptive, more-accurate, more-useful information to make citations. And that will all be metadata.

We can use that metadata to make our own citation strings that specifically represent our work - so anyone citing our work will not need to use some half-implemented, inaccurate assumption about how our work should be cited. We can be specific!

In the rest of this article, we’ll look at how we can create useful metadata and automatically use that metadata to help people create practical, useful citation strings. The result - the citation string that people will be using - will look like this:

Stormwood, A. (2025). Alex Stormwood's Website (Version 1.0.0) [Computer software]. https://github.com/AlexStormwood/alexstormwood.com

CI/CD/CC

It feels like a pretty safe statement to say that not many developers enjoy doing documentation. I’m kinda toeing the line between academia and software development, so I do enjoy documentation in my software development work - but I know not many others are in that same situation. Hell, no one that I’ve met in my life enjoys making or maintaining documentation other than me.

So, how can we get developers on board with this metadata and citations stuff? Easy - make it happen automatically, in the background!

According to a survey from the Continuous Delivery Foundation8, 83% of developers perform devops-related activities. This means that a large majority of the software development industry has a bit of exposure to CI/CD systems, processes, abilities, and so on.

From that same survey8, the developers who avoid CI/CD the most are often found in data science, desktop app development, or game development fields. 80% of game developers do have some involvement in devops - every other type of software development has an even higher percentage than that.

Again from that same survey8, freelancers - not companies, but individuals - are still mostly involved in devops tasks in some way. 21% of freelancers do not have any involvement in devops, while every other freelancer does!

All of this means that it is very, very safe for us to assume that we can show the citation automation solution - especially one where we can say “copy this, that’s all!” - and whoever we show it to will be able to understand what it is and what it is doing.

Additionally, there has been a recent movement to add “SBOM” to software projects: a software bill of materials.

An SBOM is a way for developers to identify the components of their project and more-easily audit them. If none of that sounds exciting to you, that’s okay - it’s a cybersecurity thing, and is more-applicable to government work or enterprise work. It’s essentially a paper trail, and a way for everyone involved in a project to prove that their work is safe. If you’re working on projects that are related to sensitive data like military, healthcare, or social work, then this can help your project be picked up or bought by other companies and users - because you’ve proven additional trustworthiness thanks to the SBOM.

GitHub has been working to make it easier for developers to create documents like that within their projects. In 2023, GitHub made a self-service SBOM generation system9, and specifically notes that a US government executive order from the Biden administration to improve cybersecurity helped to justify the need for that self-service system. If you are doing work with the US government, your work must be as secure as possible - and SBOMs help you do that. And GitHub helps you automate that.

Things like an SBOM fall under a recent addition to “CI/CD” known as “CC”, or “continuous compliance”. This changes the abbreviation a bit - we now have “CI/CD/CC”!

As noted by Thoughtworks in their technology innovation tracker system, the “Technology Radar”10, the whole point of continuous compliance is that your SBOMs and audit logs and security scans and other legal documentation can be managed automatically, continuously. In particular, this helps to minimise and manage the risks and costs of addressing those risks, since any issues are caught early before they become major issues.

We can treat the citation stuff in that same umbrella. It’s not source code, it’s not a deliverable part of a project, it’s not an integration thing - it’s a compliance thing.

But as implied by Thoughtworks10: this is all very new stuff, and may not be widespread in the industry yet. It’s only recently gotten on to their radar!

How to Manually Make Metadata For Your Projects

There are two steps to what we want to do to achieve this citation goal:

- Determine our project metadata.

- Use the metadata to create a citation.

There are a couple of great modern initiatives relevant to both of those steps.

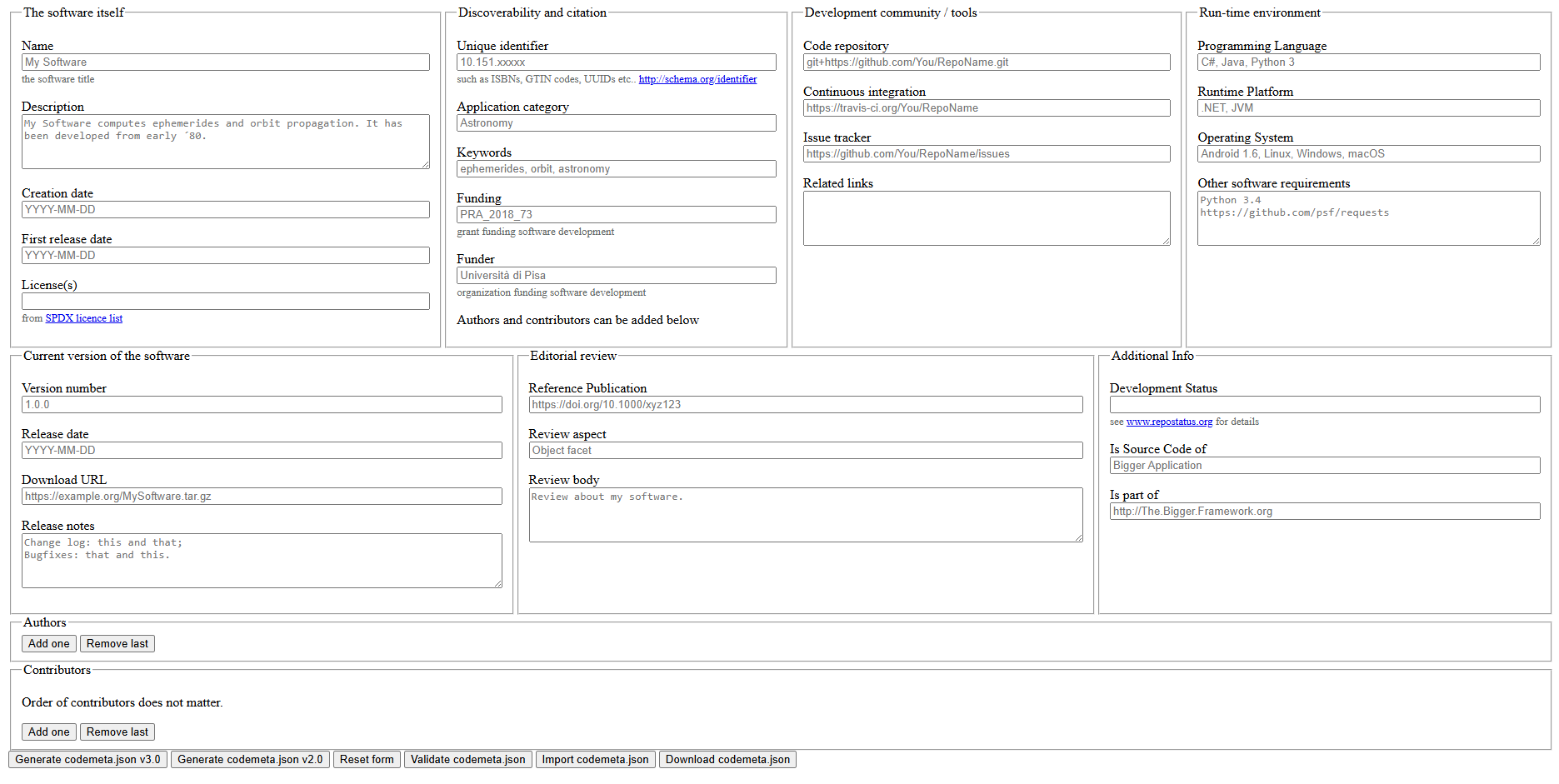

The CodeMeta JSON File

First, we have CodeMeta - an initiative first begun in 2014 to help software projects improve the metadata tracked and used for different purposes, such as research and analysis.11

CodeMeta, as a standard, allows project maintainers to declare a huge variety of data about their work. Just look at this handy generator made by Software Heritage:12:

So many fields! You can put in grant IDs to display your funding sources, information about the project language runtime, any ISBN or UUID about the project used by other content archival systems, and even put in parts like “This project is a subcomponent of this other, large project”. It’s very thorough, and the majority of the fields on that form are optional.

After filling out that page to the best of your ability, you can press a button at the bottom of the page to turn that form data into a JSON file. It should look something like this:

{

"@context": "https://doi.org/10.5063/schema/codemeta-2.0",

"@type": "SoftwareSourceCode",

"author": [

{

"@id": "https://orcid.org/0009-0008-2183-7041",

"@type": "Person",

"email": "alex@bigfootds.com",

"givenName": "Alex",

"familyName": "Stormwood",

"affiliation": {

"@type":"Organization",

"name":"BigfootDS"

}

}

],

"maintainer": [

{

"@id": "https://orcid.org/0009-0008-2183-7041",

"@type": "Person",

"email": "alex@bigfootds.com",

"givenName": "Alex",

"familyName": "Stormwood",

"affiliation": {

"@type":"Organization",

"name":"BigfootDS"

}

}

],

"codeRepository": "https://github.com/AlexStormwood/alexstormwood.com",

"url":"https://github.com/AlexStormwood/alexstormwood.com",

"dateCreated": "2025-01-26",

"dateModified": "2025-01-27",

"datePublished": "2025-01-27",

"description": "Alex Stormwood's personal website, portfolio, and blog.",

"abstract": "Alex Stormwood's personal website, portfolio, and blog.",

"downloadUrl": "https://github.com/AlexStormwood/alexstormwood.com/releases",

"keywords": [

"github"

],

"license": "https://spdx.org/licenses/MIT",

"name": "alexstormwood.com",

"programmingLanguage": "Markdown",

"runtimePlatform": "GitHub",

"version": "1.0.0",

"contIntegration": "https://github.com/AlexStormwood/alexstormwood.com/actions",

"codemeta:continuousIntegration": {

"id": "https://github.com/AlexStormwood/alexstormwood.com/actions"

},

"developmentStatus": "active",

"issueTracker": "https://github.com/AlexStormwood/alexstormwood.com/issues"

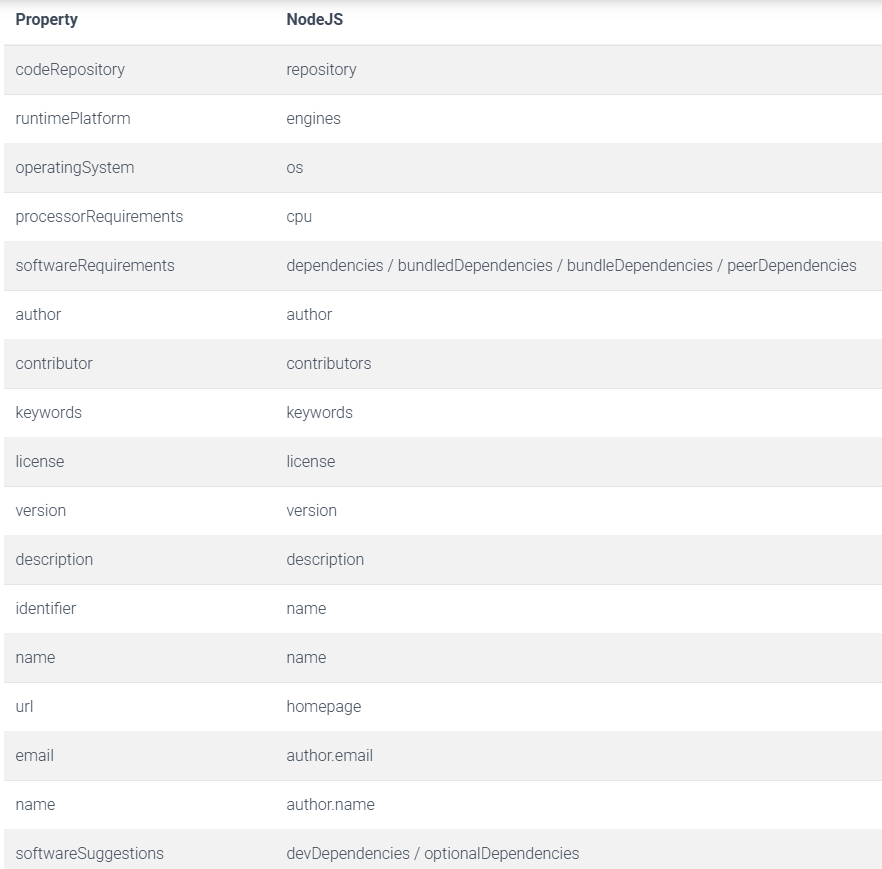

}Even if you aren’t making citation data, having a CodeMeta file like that is extremely handy. It can be used by a huge variety of systems, because CodeMeta is meant to be just a way to communicate data to others. We can see how other systems, programming languages, and tools can use CodeMeta by digging into the “crosswalk” section of CodeMeta documentation13. For example, here’s a look at the NodeJS NPM package manager crosswalk to the CodeMeta format14:

Because of the “crosswalk” data, we can more-easily figure out ways to use the CodeMeta data, or even update the CodeMeta data using data from other languages or projects. It’s a really powerful system!

The Citation File Format (CFF) File

The Citation File Format (CFF) is a key step to making it easy for others to cite your software development. It’s been around since 201715, and has a really handy GitHub integration: it’s the part that generates the “Cite this repository” button in repositories.

This file format is a plain text file made to be human- and machine-readable, intended to declare citation information for software projects and datasets.16

It looks like this:

cff-version: 1.2.0

message: "If you use this software, please cite it as below."

title: Alex Stormwood

authors:

- family-names: Stormwood

given-names: Alex

orcid: https://orcid.org/0009-0008-2183-7041

abstract: A landing page for a GitHub account.

repository-code: "https://github.com/AlexStormwood/AlexStormwood"

type: software

version: 1.0.0

license-url: "https://spdx.org/licenses/MIT"

keywords:

- github

date-released: 2025-01-27Many of the properties above map to what we’ve seen so far in CodeMeta files, and that’s a great thing. It means that we can start with one file and easily create the other. It may also be worthwhile to go and add further properties to the CFF file, as GitHub can parse different properties in a repository’s CITATION.cff file to create different outputs in a repository’s citation button.17

And yes, this CITATION.cff file must live in the root of the repository as well!

A CFF file doesn’t have to be some big lengthy document - the above example is a zero-dependency repository made by one person. Larger repositories with numerous contributors, SEO keywords, dependencies, and lengthy abstracts or descriptions will be larger, so the size of a CFF document will vary based on the project.

It’s part of why it’s such a handy thing to automate the creation and editing of that file. Let it grow as your project grows. Maintaining this file manually can become daunting or draining as a project grows, so let’s not do this manually…

How to Automatically Make Metadata For Your Projects

Enter GitHub Actions.

You could absolutely go and use other automation or CI/CD platforms to manage this stuff as well, but for this article: we’ll keep it all within GitHub’s ecosystem.

GitHub Actions is an automation system built around the YAML language, and allows developers to create “workflows” that run after certain events or triggers occur in a repository. Each workflow contains “jobs”, and they can be used to carry out actions defined in a workflow’s YAML file.

For our need here in this article, we should want a workflow that:

- Loads a repository’s contents into the workflow.

- Reads the repository’s CodeMeta file, parsing it to create a CFF file.

- Commits the CFF file into the repository.

One of the great big joys of GitHub Actions is that many developers create and share their workflow’s jobs as reusable “actions”, for others to use in their own workflows. This is a huge boon to us: other developers already created the code that parses a CodeMeta file and creates a CFF file based on that data. Other developers have also even created code that adds files and commits them to a repository. Essentially, we can make a very hands-off automation workflow to handle this citation need.

GitHub Actions workflows must live in a special folder in a repository: the .github/workflows/ directory. The .github folder lives in the root of the repository, and the workflows folder lives insid that .github folder. Workflows are YAML files, so we can name them whatever we want but they must have the .yml file extension.

So, let’s begin making that automation workflow.

This type of file contents should go into a codemeta2cff.yml file that lives in your repository’s .github/workflows/ folder, so its full repository-relative path should be .github/workflows/codemeta2cff.yml:

name: CodeMeta2CFF

run-name: Run CodeMeta2CFF after ${{github.event_name}} by ${{github.actor}}

on:

push:

paths: ['codemeta.json']

workflow_dispatch:

inputs:

reason:

description: 'Reason'

required: false

default: 'Manual trigger'

jobs:

CodeMeta2CFF:

runs-on: ubuntu-latest

steps:

- name: Checkout

uses: actions/checkout@v4

- name: Convert CFF

uses: caltechlibrary/codemeta2cff@main

- name: Commit CFF

uses: EndBug/add-and-commit@v9

with:

message: 'Add CITATION.cff for release'

add: 'CITATION.cff'That automation workflow will run whenever either of these two situations occur:

- Someone pushes a commit to the repository, where that commit specifically modifies the existing

codemeta.jsonfile found in the root of the repository. This automatically activates this workflow. - Someone clicks on a “Run this workflow” button in the GitHub repository’s Actions dashboard, manually activating this workflow.

As long as the CodeMeta file was valid, that workflow will automatically keep a repository’s CFF file and thus its citation button up-to-date.

You may note that only some properties from the CodeMeta file get mapped into the CFF file: this is a limitation in the codemeta2cff library used in the workflow, and is open to contribution in the Caltech Library “datatools” repository.18

Summary

In this article, we’ve explored the importance of metadata and how it can be used to create accurate citation data for others to use when referencing our work. We’ve looked at how to do that manually and automatically, and dug into concepts around why this stuff all matters as well.

It’s a lot to unpack, and it’s a new area of the software development industry. It’s not commonplace - yet!

But to help spread the concepts and make it easy to apply to our work, we just have to remember:

- We need a

codemeta.jsonfile. - We need an automation workflow to build a

CITATION.cfffile based on thecodemeta.jsonfile’s contents.

You could take this automated citation data system and combine with further automations not covered by this article, too. You could automate:

- Whenever a NodeJS project’s

package.jsonfile updates, update the project’scodemeta.jsonfile as well. Or the reverse direction, too! They’re both JSON, so any programming language could read and edit them, writing the new data back to their respective files! - Any automation workflow that is updating the

codemeta.jsonfile could also pull in additional data from other repositories. For example, a developer might store their “Person” entry in their GitHub account, in some special repository that is publicly accessible. This would let you pull in correct metadata about every contributor to a repository, and the contributors would just need that object stored in a file somewhere. - Whenever the

codemeta.jsonfile orCITATION.cfffile updates, a document detailing the credits of a project (e.g. for video games) would be updated by any updated metadata, such as new contributors or dependencies.

There’s a huge variety of things you can do with metadata, and creating the citation file is a really nice way to address the need for consistency in software citations and referencing. With automation, it can be easy. And with automation, it can also become a very powerful cog in a variety of a project’s other automation systems.

I hope this has been an interesting read - it was a fun rabbit-hole for me to dive into, revealing a nice bunch of software development groups, standards, and automation workflows!

And for those scrolling right to the end…

TLDR

Click this text for the two code files that all of your GitHub repositories should have!

This type of contents should go into a codemeta.json file in the root of your repository:

{

"@context": "https://doi.org/10.5063/schema/codemeta-2.0",

"@type": "SoftwareSourceCode",

"author": [

{

"@id": "https://orcid.org/0009-0008-2183-7041",

"@type": "Person",

"email": "alex@bigfootds.com",

"givenName": "Alex",

"familyName": "Stormwood",

"affiliation": {

"@type":"Organization",

"name":"BigfootDS"

}

}

],

"maintainer": [

{

"@id": "https://orcid.org/0009-0008-2183-7041",

"@type": "Person",

"email": "alex@bigfootds.com",

"givenName": "Alex",

"familyName": "Stormwood",

"affiliation": {

"@type":"Organization",

"name":"BigfootDS"

}

}

],

"codeRepository": "https://github.com/AlexStormwood/alexstormwood.com",

"url":"https://github.com/AlexStormwood/alexstormwood.com",

"dateCreated": "2025-01-26",

"dateModified": "2025-01-27",

"datePublished": "2025-01-27",

"description": "Alex Stormwood's personal website, portfolio, and blog.",

"abstract": "Alex Stormwood's personal website, portfolio, and blog.",

"downloadUrl": "https://github.com/AlexStormwood/alexstormwood.com/releases",

"keywords": [

"github"

],

"license": "https://spdx.org/licenses/MIT",

"name": "alexstormwood.com",

"programmingLanguage": "Markdown",

"runtimePlatform": "GitHub",

"version": "1.0.0",

"contIntegration": "https://github.com/AlexStormwood/alexstormwood.com/actions",

"codemeta:continuousIntegration": {

"id": "https://github.com/AlexStormwood/alexstormwood.com/actions"

},

"developmentStatus": "active",

"issueTracker": "https://github.com/AlexStormwood/alexstormwood.com/issues"

}This type of file contents should go into a codemeta2cff.yml file that lives in your repository’s .github/workflows/ folder, so its full repository-relative path should be .github/workflows/codemeta2cff.yml:

name: CodeMeta2CFF

run-name: Run CodeMeta2CFF after ${{github.event_name}} by ${{github.actor}}

on:

push:

paths: ['codemeta.json']

workflow_dispatch:

inputs:

reason:

description: 'Reason'

required: false

default: 'Manual trigger'

jobs:

CodeMeta2CFF:

runs-on: ubuntu-latest

steps:

- name: Checkout

uses: actions/checkout@v4

- name: Convert CFF

uses: caltechlibrary/codemeta2cff@main

- name: Commit CFF

uses: EndBug/add-and-commit@v9

with:

message: 'Add CITATION.cff for release'

add: 'CITATION.cff'That will automatically keep this citation button up-to-date on your repositories:

References

Footnotes

-

Valve. (2009). Meet the Sniper. In YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9NZDwZbyDus ↩

-

About CITATION files - GitHub Docs. (2017). GitHub Docs. https://docs.github.com/en/repositories/managing-your-repositorys-settings-and-features/customizing-your-repository/about-citation-files ↩

-

BigfootDS. (2024, October 19). GitHub - BigfootDS/supercamo: Camo-inspired ODM for NeDB, built specifically for BigfootDS’ needs. GitHub. https://github.com/BigfootDS/supercamo ↩ ↩2 ↩3

-

About CITATION files - GitHub Docs. (2017). GitHub Docs. https://docs.github.com/en/repositories/managing-your-repositorys-settings-and-features/customizing-your-repository/about-citation-files#citing-something-other-than-software ↩

-

UNSW Sydney. (2019, October 28). Why Is Referencing Important? UNSW Sydney. https://www.student.unsw.edu.au/why-referencing-important ↩

-

Zenodo - Research. Shared. (2018). Zenodo.org. https://zenodo.org/ ↩

-

Australian Bureau of Statistics. (2023, February 2). Metadata | Australian Bureau of Statistics. https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/understanding-statistics/statistical-terms-and-concepts/metadata ↩

-

SlashData. (2024, August 19). State of CI/CD Report 2024. CD Foundation. https://cd.foundation/state-of-cicd-2024/ ↩ ↩2 ↩3

-

Tooley, E. (2023, March 28). Introducing self-service SBOMs. The GitHub Blog. https://github.blog/enterprise-software/governance-and-compliance/introducing-self-service-sboms/ ↩

-

Thoughtworks. (2024). Continuous compliance | Technology Radar | Thoughtworks Australia. Thoughtworks. https://www.thoughtworks.com/en-au/radar/techniques/continuous-compliance ↩ ↩2

-

codemeta. (2023, July 13). GitHub - codemeta/codemeta: Minimal metadata schemas for science software and code, in JSON-LD. GitHub. https://github.com/codemeta/codemeta ↩

-

Software Heritage. (2025). CodeMeta generator. Github.io. https://codemeta.github.io/codemeta-generator/ ↩ ↩2

-

codemeta. (2025). Crosswalk - The CodeMeta Project. Github.io. https://codemeta.github.io/crosswalk/ ↩

-

codemeta. (2025b). Crosswalk for NodeJS package.json - The CodeMeta Project. Github.io. https://codemeta.github.io/crosswalk/node/ ↩ ↩2

-

Druskat, S., Spaaks, J. H., Chue Hong, N., Haines, R., Baker, J., Bliven, S., Willighagen, E., Pérez-Suárez, D., & Konovalov, O. (2021). Citation File Format (Version 1.2.0) [Computer software]. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.5171937 ↩

-

Druskat, S. (2021). Citation File Format (CFF). Citation File Format (CFF). https://citation-file-format.github.io/ ↩

-

GitHub. (2017). About CITATION files - GitHub Docs. GitHub Docs. https://docs.github.com/en/repositories/managing-your-repositorys-settings-and-features/customizing-your-repository/about-citation-files ↩

-

Morrell, T. E. (2024). codemeta2cff (Version 0.3.3) [Computer software]. https://doi.org/10.22002/q79s0-7w020 ↩